如果你也在 怎样代写贝叶斯分析Bayesian Analysis这个学科遇到相关的难题,请随时右上角联系我们的24/7代写客服。

贝叶斯分析,一种统计推断方法(以英国数学家托马斯-贝叶斯命名),允许人们将关于人口参数的先验信息与样本所含信息的证据相结合,以指导统计推断过程。

statistics-lab™ 为您的留学生涯保驾护航 在代写贝叶斯分析Bayesian Analysis方面已经树立了自己的口碑, 保证靠谱, 高质且原创的统计Statistics代写服务。我们的专家在代写贝叶斯分析Bayesian Analysis代写方面经验极为丰富,各种代写贝叶斯分析Bayesian Analysis相关的作业也就用不着说。

我们提供的贝叶斯分析Bayesian Analysis及其相关学科的代写,服务范围广, 其中包括但不限于:

- Statistical Inference 统计推断

- Statistical Computing 统计计算

- Advanced Probability Theory 高等概率论

- Advanced Mathematical Statistics 高等数理统计学

- (Generalized) Linear Models 广义线性模型

- Statistical Machine Learning 统计机器学习

- Longitudinal Data Analysis 纵向数据分析

- Foundations of Data Science 数据科学基础

统计代写|贝叶斯分析代写Bayesian Analysis代考|Basics of Bayes for Reasoning about Legal Evidence

Probabilistic reasoning of legal evidence often boils down to the simple BN model shown in Figure 15.1. The hypothesis $H$ is a statement whose truth value we seek to determine, but is generally unknown-and which may never be known with certainty.

Examples include:

“Defendant is guilty of the crime as charged” (this is an example of what is called an offense-level hypothesis, but also called the ultimate hypothesis, since in many criminal cases, it is ultimately the only hypothesis we are really interested in)

- “Defendant was at the crime scene” (this is an example of what is often referred to as an activity-level hypothesis)

- “Defendant was the source of DNA found at the crime scene” (this is an example of what is often referred to as a source-level hypothesis)

The evidence $E$ is a statement that claims to support either the hypothesis $H$ or the alternative hypothesis (which is the negation of $H$ ). For example, a statement by an eyewitness who claims he or she saw the defendant at the scene of the crime might be considered evidence to support any of the above types of hypotheses. Of special interest is forensic evidence, such as the example shown in the explicit BN of Figure 15.2. In this example, we assume:

- The evidence $E$ is a DNA trace found at the scene of the crime (for simplicity, we assume the crime was committed on an island with 10,000 people who therefore represent the entire set of possible suspects).

- The defendant was arrested and some of his DNA was sampled and analyzed (see Box 15.7 for the necessary background about DNA profiles).

统计代写|贝叶斯分析代写Bayesian Analysis代考|The Problems with Trying to Avoid Using Prior Probabilities with the Likelihood Ratio

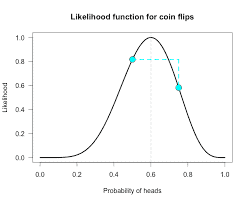

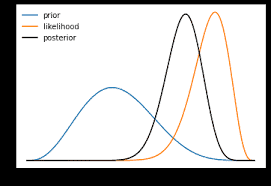

It is possible to avoid the delicate and controversial issue of assigning a subjective prior probability to the ultimate hypothesis (or, indeed, to any specific hypothesis) if we instead are prepared to focus only on the “probabilistic value” of the evidence. Recall from Chapter 6 and the sidebar that the impact of any single piece of evidence $E$ on a hypothesis $H$ can be determined by considering only the likelihood ratio of $E$, which is the probability of seeing that evidence if $H$ is true (e.g., “defendant is guilty”) divided by the probability of seeing that evidence if $H$ is not true (e.g., “defendant is not guilty”), that is, $P(E \mid H)$ divided by $P(E \mid \operatorname{not} H)$.

In the DNA example of Figure 15.2, the likelihood ratio is 1000 (since the prosecution likelihood is 1 and the defense likelihood is $1 / 1000$ ). So this particular evidence is clearly very probative in favor of the prosecution hypothesis (that the suspect is the source of the DNA found at the crime scene). In court, the DNA expert would be able to present this likelihood ratio without making any assertions about the prior probability of the prosecution hypothesis by simply saying:

We are 1000 more times likely to find this evidence under the assumption that the prosecution hypothesis is true than under the assumption that the defense hypothesis is true.

While this is helpful, the extent to which it can lead a judge or jury to “believe” the prosecution hypothesis still depends on the prior probability; as explained in Box 15.9, we use the “odds” version of Bayes (that we introduced in Chapter 6) to make the necessary conclusions.

In summary, whether the likelihood ratio of 1000 -or even 10 million-“swings” the odds sufficiently in favor of the prosecution hypothesis depends entirely on the prior odds. So, while the likelihood ratio enables us to assess the impact of evidence on $H$ without having to consider the prior probability of $H$, it is clear from the above DNA example that the prior probability must ultimately be considered before returning a verdict. With or without a Bayesian approach, jurors and judges intuitively make assumptions about the prior probability and adjust this in light of the evidence. A key benefit of the Bayesian approach is to make explicit the ramifications of different prior assumptions. So, a judge could state something like the following where, say, the evidence has a likelihood ratio of one million:

Whatever you believed before about the possible guilt of the defendant, the evidence is one million times more likely if the defendant is guilty than if he is innocent. So, if you believed at the beginning that there was a 50:50 chance that the defendant was innocent, then it is only rational for you to conclude with the evidence that there is only a million to one chance the defendant really is innocent. On this basis you should return a guilty verdict. But if you believed at the beginning that the defendant is no more likely to be guilty than a million other people in the area, then it is only rational for you to conclude with the evidence that there is a $50: 50$ chance the defendant really is innocent. On that basis you should return a not guilty verdict.

贝叶斯分析代考

统计代写|贝叶斯分析代写Bayesian Analysis代考|Basics of Bayes for Reasoning about Legal Evidence

法律证据的概率推理通常归结为图 15.1 所示的简单 BN 模型。假设H是一个陈述,我们试图确定其真值,但通常是未知的——而且可能永远无法确定。

示例包括:

“被告犯有被指控的罪行”(这是所谓的犯罪级别假设的示例,但也称为最终假设,因为在许多刑事案件中,它最终是我们真正的唯一假设有兴趣)

- “被告在犯罪现场”(这是通常被称为活动水平假设的一个例子)

- “被告是在犯罪现场发现的 DNA 的来源”(这是通常被称为源级假设的一个例子)

证据和是声称支持假设的陈述H或替代假设(这是否定的H). 例如,目击者声称他或她在犯罪现场看到被告的陈述可能被视为支持上述任何类型假设的证据。特别感兴趣的是取证证据,例如图 15.2 的显式 BN 中显示的示例。在这个例子中,我们假设:

- 证据和是在犯罪现场发现的 DNA 痕迹(为简单起见,我们假设犯罪发生在一个有 10,000 人的岛上,因此代表了所有可能的嫌疑人)。

- 被告被捕,对他的一些 DNA 进行了取样和分析(有关 DNA 图谱的必要背景,请参见专栏 15.7)。

统计代写|贝叶斯分析代写Bayesian Analysis代考|The Problems with Trying to Avoid Using Prior Probabilities with the Likelihood Ratio

如果我们只关注证据的“概率值”,就可以避免将主观先验概率分配给最终假设(或者实际上,分配给任何特定假设)这一微妙而有争议的问题。回想一下第 6 章和侧边栏,任何单个证据的影响和假设H可以通过仅考虑似然比来确定和,这是看到该证据的概率,如果H是真的(例如,“被告有罪”)除以看到该证据的概率,如果H是不正确的(例如,“被告无罪”),也就是说,P(和∣H)除以P(和∣不是H).

在图 15.2 的 DNA 示例中,似然比为 1000(因为起诉可能性为 1,而辩护可能性为1/1000). 因此,这一特定证据显然非常有利于起诉假设(嫌疑人是在犯罪现场发现的 DNA 的来源)。在法庭上,DNA 专家将能够在不对起诉假设的先验概率做出任何断言的情况下提出这种似然比,只需简单地说:在假设

起诉假设为真的情况下,我们找到该证据的可能性是 1000 倍在防御假说成立的假设下。

虽然这很有帮助,但它能在多大程度上让法官或陪审团“相信”起诉假设仍然取决于先验概率;正如专栏 15.9 中所解释的,我们使用贝叶斯的“几率”版本(我们在第 6 章中介绍过)来得出必要的结论。

总而言之,1000 甚至 1000 万的似然比是否“摇摆”概率足以支持起诉假设完全取决于先验概率。因此,虽然似然比使我们能够评估证据对H无需考虑先验概率H,从上面的DNA例子中可以看出,在返回判决之前最终必须考虑先验概率。无论是否使用贝叶斯方法,陪审员和法官都会凭直觉对先验概率做出假设,并根据证据对其进行调整。贝叶斯方法的一个主要好处是明确不同先验假设的后果。因此,法官可以陈述如下内容,例如,证据的似然比为一百万:

无论您之前对被告可能有罪的看法如何,如果被告有罪,证据的可能性是他无罪的一百万倍。因此,如果您一开始就认为被告有 50:50 的可能性是无辜的,那么您只能合理地得出结论,证据表明被告真正无罪的可能性只有百万分之一。在此基础上,您应该作出有罪判决。但是,如果您一开始就认为被告人有罪的可能性并不比该地区的其他 100 万人高,那么您就只能理性地得出结论,证据表明存在50:50被告真的是无辜的。在此基础上,您应该作出无罪判决。

统计代写请认准statistics-lab™. statistics-lab™为您的留学生涯保驾护航。

金融工程代写

金融工程是使用数学技术来解决金融问题。金融工程使用计算机科学、统计学、经济学和应用数学领域的工具和知识来解决当前的金融问题,以及设计新的和创新的金融产品。

非参数统计代写

非参数统计指的是一种统计方法,其中不假设数据来自于由少数参数决定的规定模型;这种模型的例子包括正态分布模型和线性回归模型。

广义线性模型代考

广义线性模型(GLM)归属统计学领域,是一种应用灵活的线性回归模型。该模型允许因变量的偏差分布有除了正态分布之外的其它分布。

术语 广义线性模型(GLM)通常是指给定连续和/或分类预测因素的连续响应变量的常规线性回归模型。它包括多元线性回归,以及方差分析和方差分析(仅含固定效应)。

有限元方法代写

有限元方法(FEM)是一种流行的方法,用于数值解决工程和数学建模中出现的微分方程。典型的问题领域包括结构分析、传热、流体流动、质量运输和电磁势等传统领域。

有限元是一种通用的数值方法,用于解决两个或三个空间变量的偏微分方程(即一些边界值问题)。为了解决一个问题,有限元将一个大系统细分为更小、更简单的部分,称为有限元。这是通过在空间维度上的特定空间离散化来实现的,它是通过构建对象的网格来实现的:用于求解的数值域,它有有限数量的点。边界值问题的有限元方法表述最终导致一个代数方程组。该方法在域上对未知函数进行逼近。[1] 然后将模拟这些有限元的简单方程组合成一个更大的方程系统,以模拟整个问题。然后,有限元通过变化微积分使相关的误差函数最小化来逼近一个解决方案。

tatistics-lab作为专业的留学生服务机构,多年来已为美国、英国、加拿大、澳洲等留学热门地的学生提供专业的学术服务,包括但不限于Essay代写,Assignment代写,Dissertation代写,Report代写,小组作业代写,Proposal代写,Paper代写,Presentation代写,计算机作业代写,论文修改和润色,网课代做,exam代考等等。写作范围涵盖高中,本科,研究生等海外留学全阶段,辐射金融,经济学,会计学,审计学,管理学等全球99%专业科目。写作团队既有专业英语母语作者,也有海外名校硕博留学生,每位写作老师都拥有过硬的语言能力,专业的学科背景和学术写作经验。我们承诺100%原创,100%专业,100%准时,100%满意。

随机分析代写

随机微积分是数学的一个分支,对随机过程进行操作。它允许为随机过程的积分定义一个关于随机过程的一致的积分理论。这个领域是由日本数学家伊藤清在第二次世界大战期间创建并开始的。

时间序列分析代写

随机过程,是依赖于参数的一组随机变量的全体,参数通常是时间。 随机变量是随机现象的数量表现,其时间序列是一组按照时间发生先后顺序进行排列的数据点序列。通常一组时间序列的时间间隔为一恒定值(如1秒,5分钟,12小时,7天,1年),因此时间序列可以作为离散时间数据进行分析处理。研究时间序列数据的意义在于现实中,往往需要研究某个事物其随时间发展变化的规律。这就需要通过研究该事物过去发展的历史记录,以得到其自身发展的规律。

回归分析代写

多元回归分析渐进(Multiple Regression Analysis Asymptotics)属于计量经济学领域,主要是一种数学上的统计分析方法,可以分析复杂情况下各影响因素的数学关系,在自然科学、社会和经济学等多个领域内应用广泛。

MATLAB代写

MATLAB 是一种用于技术计算的高性能语言。它将计算、可视化和编程集成在一个易于使用的环境中,其中问题和解决方案以熟悉的数学符号表示。典型用途包括:数学和计算算法开发建模、仿真和原型制作数据分析、探索和可视化科学和工程图形应用程序开发,包括图形用户界面构建MATLAB 是一个交互式系统,其基本数据元素是一个不需要维度的数组。这使您可以解决许多技术计算问题,尤其是那些具有矩阵和向量公式的问题,而只需用 C 或 Fortran 等标量非交互式语言编写程序所需的时间的一小部分。MATLAB 名称代表矩阵实验室。MATLAB 最初的编写目的是提供对由 LINPACK 和 EISPACK 项目开发的矩阵软件的轻松访问,这两个项目共同代表了矩阵计算软件的最新技术。MATLAB 经过多年的发展,得到了许多用户的投入。在大学环境中,它是数学、工程和科学入门和高级课程的标准教学工具。在工业领域,MATLAB 是高效研究、开发和分析的首选工具。MATLAB 具有一系列称为工具箱的特定于应用程序的解决方案。对于大多数 MATLAB 用户来说非常重要,工具箱允许您学习和应用专业技术。工具箱是 MATLAB 函数(M 文件)的综合集合,可扩展 MATLAB 环境以解决特定类别的问题。可用工具箱的领域包括信号处理、控制系统、神经网络、模糊逻辑、小波、仿真等。