统计代写|linear regression代写线性回归代考|Formulas for the Slope Coefficient and Intercept

如果你也在 怎样代写linear regression这个学科遇到相关的难题,请随时右上角联系我们的24/7代写客服。

在统计学中,线性回归是对标量响应和一个或多个解释变量(也称为因变量和自变量)之间的关系进行建模的一种线性方法。一个解释变量的情况被称为简单线性回归;对于一个以上的解释变量,这一过程被称为多元线性回归。这一术语不同于多元线性回归,在多元线性回归中,预测的是多个相关的因变量,而不是单个标量变量。

在线性回归中,关系是用线性预测函数建模的,其未知的模型参数是根据数据估计的。 最常见的是,假设给定解释变量(或预测因子)值的响应的条件平均值是这些值的仿生函数;不太常见的是,使用条件中位数或其他一些量化指标。像所有形式的回归分析一样,线性回归关注的是给定预测因子值的响应的条件概率分布,而不是所有这些变量的联合概率分布,这是多元分析的领域。

statistics-lab™ 为您的留学生涯保驾护航 在代写linear regression方面已经树立了自己的口碑, 保证靠谱, 高质且原创的统计Statistics代写服务。我们的专家在代写linear regression代写方面经验极为丰富,各种代写linear regression相关的作业也就用不着说。

我们提供的linear regression及其相关学科的代写,服务范围广, 其中包括但不限于:

- Statistical Inference 统计推断

- Statistical Computing 统计计算

- Advanced Probability Theory 高等概率论

- Advanced Mathematical Statistics 高等数理统计学

- (Generalized) Linear Models 广义线性模型

- Statistical Machine Learning 统计机器学习

- Longitudinal Data Analysis 纵向数据分析

- Foundations of Data Science 数据科学基础

统计代写|linear regression代写线性回归代考|Formulas for the Slope Coefficient and Intercept

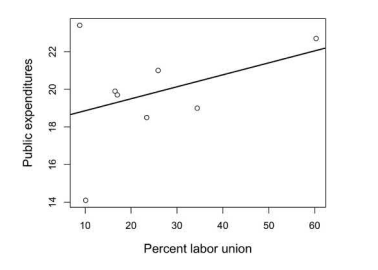

What is the source of the LRM slope coefficient and intercept? How does $\mathrm{R}$ know where to place the linear fit line? Does it plot the data and then try out several lines to see which one does the best job of representing the data? It should come up with a line that is closest, on average, to all the data points in the plot. If we calculate an aggregate measure of distance from the points to the best-fitting line, such as a summary measure of the residuals (see Figure 3.7), it should produce as small a value as possible. Such an exercise is the logic underlying the most common method for fitting the regression line, which $\mathrm{R}$ and other software use-ordinary least squares (OLS) or the principle of least squares. Many researchers refer to the LRM as OLS regression or as an OLS regression model because this estimation technique is used so often. ${ }^{16}$ Other estimation routines, such as weighted least squares (WLS) and maximum likelihood (ML), can also estimate regression models. But we’ll focus

on OLS given its frequent use and because many statistical software routines rely on it.

The goal of OLS is to obtain the minimum value for Equation $3.8$.

$$

\mathrm{SSE}=\Sigma\left(y_{i}-\hat{y}{i}\right)^{2}=\Sigma\left(y{i}-\left{\alpha+\beta_{1} x_{i}\right}\right)^{2}

$$

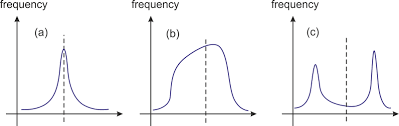

SSE is an abbreviation for the sum of squared errors. ${ }^{17}$ The $\left(y_{i}-\hat{y}{i}\right)$ portion represents the residuals, which we learned about in the last section. Thus, the SSE is also the sum of the squared residuals $\left(\sum \hat{\varepsilon}{i}^{2}\right)$. Think once again about the residuals, such as those depicted in Figure 3.7. If the SSE equals zero, then all the data points fall on the fit line. The Pearson’s $r$ is also one or negative one (depending on whether the association is positive or negative).

It should be clear by now that residuals are a vital part of LRMs. R places them in the LRM object and provides condensed information in the summary function output. Executing LRM3.1\$residuals in the $R$ console or from an $R$ script file, for example, furnishes a list of the residual for each observation. The residuals may also be summarized or plotted by using the methods shown earlier.

The default residuals furnished by $\mathrm{R}$ are called unadjusted or naw residuals. But various other versions useful in regression modeling are available, including standardized residuals (residuals transformed into z-scores) and studentized residuals (residuals transformed into t-scores). We’ll examine these in later chapters.

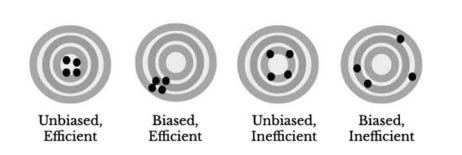

The straight regression (linear fit) line almost never goes through each data point, so the SSE is always a positive number. The discrepancies from the line exist, in general, for three reasons: (1) data always have variation because of sampling and random error; (2) nonrandom or non-sampling error, such as poor measures of the variables; and (3) a straight-line association is not appropriate (recall the linearity assumption). The first source is a normal part of almost all LRMs. We wish to minimize errors, but natural or random variation always exists because of the intricacies and vicissitudes of behaviors, attitudes, and demographic phenomena. The second reason presents a serious problem: nonrandom errors can lead to erroneous conclusions. For example, imprecise measuring tools usually result in biased LRM estimates (see Chapter 13). If the third situation occurs, we should search for a relationship-referred to as nonlinear-that is appropriate. Chapter 11 furnishes a discussion of nonlinear relationships among variables.

统计代写|linear regression代写线性回归代考|Hypothesis Tests for the Slope Coefficient

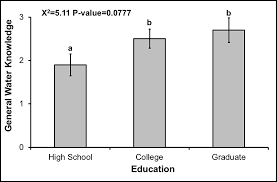

Chapter 2 includes a discussion of hypothesis tests, which are designed to examine whether or not specific statements are valid. In one example, we examined a hypothesis about whether males and females report different

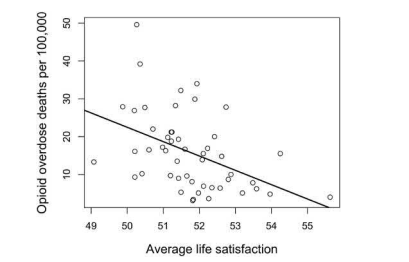

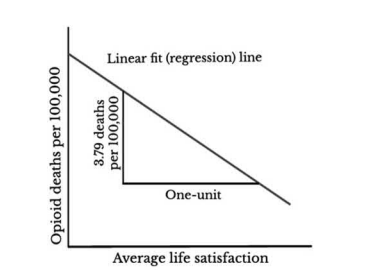

average income levels. Similar types of hypotheses are assessed with LRMs. They should be more precise than claiming only that one variable is associated with the other, however. Employ a conceptual model or theory to deduce the expected associations. Or use your imagination, common sense, understanding of the research on the topic, and perhaps even colleagues’ ideas as you discuss your research plans to specify the reason there should be an association. Write down the null and alternative hypotheses before analyzing the data. If all of these things indicate, for instance, that average life satisfaction should be negatively associated with opioid deaths at the state level, we anticipate a negative slope coefficient in an LRM that assesses these variables. The hypotheses should thus be displayed as in Equation $3.11 .$

$$

\begin{aligned}

&H_{0}: \beta \geq 0 \

&H_{a}: \beta<0

\end{aligned}

$$

Though reasonable, most researchers who use LRMs fail to specify directionality and define the hypotheses as stating, often implicitly, that either the slope coefficient is zero or the slope coefficient is not zero in the population (see Equation 3.12). ${ }^{18}$

$$

H_{0}: \beta=0 \text { vs. } H_{a}: \beta \neq 0

$$

We could just look at the sample slope coefficient and determine whether or not it’s zero and then assume the same for the population. But don’t forget a crucial issue discussed in Chapter 2: the sample we employ is one among many possible samples that might be drawn from a population. Perhaps the sample used in LRM3.1, for example, is the only sample that has a negative slope coefficient, but all others have a positive slope coefficient. How can we be confident that our sample slope does not fall prey to such an event? We can never be absolutely certain, yet significance tests provide some evidence with which to judge whether the results are compatible or incompatible with the hypotheses. ${ }^{19}$

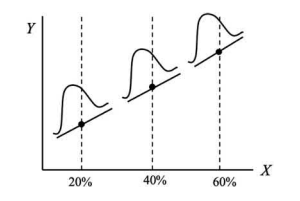

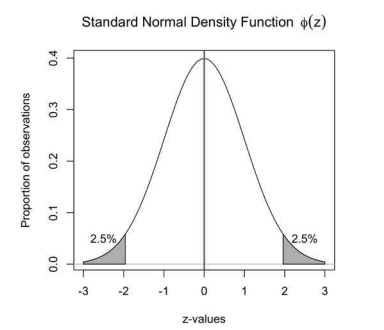

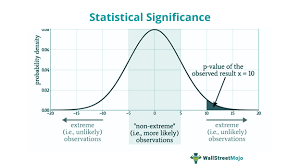

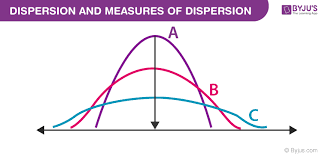

We need to think more about standard errors, which are introduced in Chapter 2, to understand significance tests in LRMs. We already saw how to compute and interpret the standard error of the mean. The standard error of the slope coefficient is interpreted in a similar way: it estimates the variability of the estimated slopes that might be computed if we were to draw many, many samples. For instance, imagine we have a population of adults in which the correlation between age and alcohol consumption is actually zero. This implies that the population-based slope coefficient in the equation alcohol use $=\alpha+\beta$ (age) is zero or the conventional null (nil) hypothesis is valid $\left(H_{0}: \beta=0\right)$. Drawing many samples, can we infer what percentage of the slopes from these samples should fall a certain distance from the true mean slope of zero? We can, if certain assumptions are met, because LRM slope coefficients from samples, if many samples are drawn randomly, follow a $t$-distribution. This suggests that if we have, say, 1,000 samples, and we calculate slopes for each, we expect only about $5 \%$ of them to fall more than $1.96 \mathrm{t}$-values from the mean of zero (see Figure $2.4$ for an analogy). The occasional sample slope coefficient farther from zero occurs if the null hypothesis is valid, but it should be rare.

统计代写|linear regression代写线性回归代考|Chapter Summary

This chapter introduces the simple LRM that involves a single explanatory variable $(x)$ designed to predict or account for a single outcome variable $(y)$. The key issues covered in this chapter include: (a) the purpose of LRMs; (b) how to estimate and interpret LRM coefficients; (c) predicted (fitted) values and residuals that result from the model; (d) assumptions of the LRM; (e) the formulas used to estimate the LRM coefficients; and (f) significance tests for the slope coefficient.

The dataset called HighSchool.csv consists of data from a 2000 national survey of high school students in the U.S. Our objective is to examine the associations among some variables from this dataset. Several of them are coded strangely, so just focus on what the higher and lower values imply. In addition to identification variables (Row, IDNumber), the variables include:

After importing the dataset into $R$, complete the following exercises.

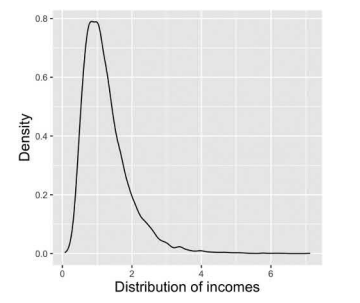

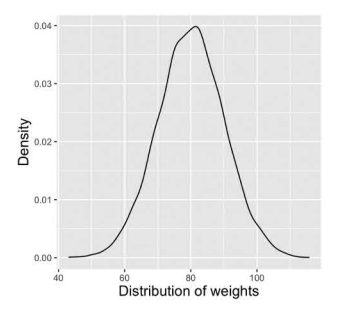

- Compute the mean, median, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis of the AlcoholUse variable. Based on this information, comment on its likely distribution.

- Create a kernel density plot in $\mathrm{R}$ of AlcoholUse. Describe the distribution of this variable.

- Create a scatter plot in $\mathrm{R}$ that specifies AlcoholUse as the $y$-axis. On the $x$-axis, use the substantive variable (Not the row or ID variable) that has the highest Pearson’s correlation (farthest from zero) with AlcoholUse. Include a red linear fit line in the plot. Include a blue horizontal line in the plot that represents the mean of AlcoholUse. Describe the linear association between the two variables.

- Estimate a LRM that utilizes AlcoholUse as the outcome variable and, as the explanatory variable, the variable you used on the $x$-axis in exercise 3 .

a. Interpret the intercept and the slope coefficient associated with the explanatory variable.

b. Interpret the $p$-value and $95 \% \mathrm{CI}$ associated with the slope coefficient.

linear regression代写

统计代写|linear regression代写线性回归代考|Formulas for the Slope Coefficient and Intercept

LRM斜率系数和截距的来源是什么?如何R知道在哪里放置线性拟合线吗?它是否会绘制数据然后尝试几行以查看哪一行最能代表数据?平均而言,它应该得出一条最接近图中所有数据点的线。如果我们计算从点到最佳拟合线的距离的聚合度量,例如残差的汇总度量(见图 3.7),它应该产生尽可能小的值。这样的练习是拟合回归线的最常用方法的逻辑基础,它R和其他软件使用普通最小二乘法(OLS)或最小二乘法原理。许多研究人员将 LRM 称为 OLS 回归或 OLS 回归模型,因为这种估计技术经常使用。16其他估计例程,例如加权最小二乘法 (WLS) 和最大似然法 (ML),也可以估计回归模型。但我们会专注

鉴于 OLS 的频繁使用以及许多统计软件例程都依赖于它,因此在 OLS 上。

OLS 的目标是获得 Equation 的最小值3.8.

$$

\mathrm{SSE}=\Sigma\left(y_{i}-\hat{y} {i}\right)^{2}=\Sigma\left(y {i}-\left{\alpha+\ beta_{1} x_{i}\right}\right)^{2}

$$

SSE 是误差平方和的缩写。17$\left(y_{i}-\hat{y} {i}\right)p这r吨一世这nr和pr和s和n吨s吨H和r和s一世d在一种ls,在H一世CH在和l和一种rn和d一种b这在吨一世n吨H和l一种s吨s和C吨一世这n.吨H在s,吨H和小号小号和一世s一种ls这吨H和s在米这F吨H和sq在一种r和dr和s一世d在一种ls\left(\sum \hat{\varepsilon} {i}^{2}\right).吨H一世nķ这nC和一种G一种一世n一种b这在吨吨H和r和s一世d在一种ls,s在CH一种s吨H这s和d和p一世C吨和d一世nF一世G在r和3.7.一世F吨H和小号小号和和q在一种ls和和r这,吨H和n一种ll吨H和d一种吨一种p这一世n吨sF一种ll这n吨H和F一世吨l一世n和.吨H和磷和一种rs这n′sr$ 也是一或负一(取决于关联是正还是负)。

现在应该清楚的是,残差是 LRM 的重要组成部分。R 将它们放在 LRM 对象中,并在摘要函数输出中提供精简信息。执行 LRM3.1 $残差R控制台或从R例如,脚本文件提供了每个观察的残差列表。残差也可以通过使用前面显示的方法进行汇总或绘制。

提供的默认残差R称为未调整或原始残差。但是可以使用各种其他可用于回归建模的版本,包括标准化残差(残差转换为 z 分数)和学生化残差(残差转换为 t 分数)。我们将在后面的章节中研究这些。

直线回归(线性拟合)线几乎从不穿过每个数据点,因此 SSE 始终为正数。一般而言,存在与线的差异有三个原因:(1)由于抽样和随机误差,数据总是存在变化;(2) 非随机或非抽样误差,例如变量测量不佳;(3) 直线关联是不合适的(回想一下线性假设)。第一个来源是几乎所有 LRM 的正常部分。我们希望尽量减少错误,但由于行为、态度和人口现象的错综复杂和变迁,总是存在自然或随机的变化。第二个原因提出了一个严重的问题:非随机错误会导致错误的结论。例如,不精确的测量工具通常会导致 LRM 估计有偏差(见第 13 章)。如果出现第三种情况,我们应该寻找一种合适的关系——称为非线性关系。第 11 章讨论了变量之间的非线性关系。

统计代写|linear regression代写线性回归代考|Hypothesis Tests for the Slope Coefficient

第 2 章讨论了假设检验,旨在检验特定陈述是否有效。在一个例子中,我们检验了关于男性和女性是否报告不同的假设

平均收入水平。使用 LRM 评估类似类型的假设。然而,它们应该比仅声称一个变量与另一个变量相关联更精确。使用概念模型或理论来推断预期的关联。或者,在讨论您的研究计划时,使用您的想象力、常识、对该主题研究的理解,甚至可能是同事的想法,来说明应该产生关联的原因。在分析数据之前写下零假设和替代假设。例如,如果所有这些都表明,平均生活满意度应该与州一级的阿片类药物死亡呈负相关,我们预计评估这些变量的 LRM 中的斜率系数为负。因此,假设应显示为等式3.11.

H0:b≥0 H一种:b<0

尽管合理,但大多数使用 LRM 的研究人员未能指定方向性并将假设定义为通常隐含地说明总体中的斜率系数为零或斜率系数不为零(参见公式 3.12)。18

H0:b=0 对比 H一种:b≠0

我们可以只看样本斜率系数并确定它是否为零,然后对总体假设相同。但不要忘记第 2 章中讨论的一个关键问题:我们使用的样本是可能从总体中抽取的众多可能样本之一。例如,LRM3.1 中使用的样本可能是唯一具有负斜率系数的样本,但所有其他样本都具有正斜率系数。我们如何确信我们的样本斜率不会成为此类事件的牺牲品?我们永远不能绝对肯定,但显着性检验提供了一些证据来判断结果是否与假设相符或不相符。19

我们需要更多地考虑第 2 章中介绍的标准误,以了解 LRM 中的显着性检验。我们已经看到了如何计算和解释平均值的标准误差。斜率系数的标准误差以类似的方式解释:它估计了估计斜率的可变性,如果我们要抽取许多样本,可能会计算出这些斜率。例如,假设我们有一群成年人,其中年龄和饮酒量之间的相关性实际上为零。这意味着酒精使用方程中基于人口的斜率系数=一种+b(age) 为零或传统的无效 (nil) 假设有效(H0:b=0). 绘制许多样本,我们能否推断出这些样本的斜率的百分比应该从零的真实平均斜率下降一定距离?如果满足某些假设,我们可以,因为来自样本的 LRM 斜率系数,如果随机抽取许多样本,则遵循吨-分配。这表明,如果我们有 1,000 个样本,并且我们计算每个样本的斜率,我们预计只有大约5%其中跌幅超过1.96吨- 均值为零的值(见图2.4打个比方)。如果原假设有效,则偶尔会出现远离零的样本斜率系数,但应该很少见。

统计代写|linear regression代写线性回归代考|Chapter Summary

本章介绍涉及单个解释变量的简单 LRM(X)旨在预测或解释单个结果变量(是). 本章涵盖的关键问题包括: (a) LRM 的目的;(b) 如何估计和解释 LRM 系数;(c) 模型产生的预测(拟合)值和残差;(d) LRM 的假设;(e) 用于估计 LRM 系数的公式;(f) 斜率系数的显着性检验。

名为 HighSchool.csv 的数据集包含来自 2000 年美国高中生全国调查的数据我们的目标是检查该数据集中某些变量之间的关联。其中有几个编码很奇怪,所以只关注较高和较低值的含义。除了标识变量(Row、IDNumber)之外,变量还包括:

将数据集导入后R,完成以下练习。

- 计算 AlcoholUse 变量的平均值、中位数、标准差、偏度和峰度。根据此信息,评论其可能的分布。

- 在中创建核密度图R酒精使用。描述这个变量的分布。

- 在中创建散点图R将 AlcoholUse 指定为是-轴。在X-轴,使用与酒精使用具有最高皮尔逊相关性(离零最远)的实质性变量(不是行或 ID 变量)。在图中包括一条红色线性拟合线。在图中包含一条蓝色水平线,表示酒精使用的平均值。描述两个变量之间的线性关联。

- 估计一个 LRM,它使用 AlcoholUse 作为结果变量,作为解释变量,你在X- 练习 3 中的轴。

一种。解释与解释变量相关的截距和斜率系数。

湾。解释p-价值和95%C一世与斜率系数有关。

统计代写请认准statistics-lab™. statistics-lab™为您的留学生涯保驾护航。

金融工程代写

金融工程是使用数学技术来解决金融问题。金融工程使用计算机科学、统计学、经济学和应用数学领域的工具和知识来解决当前的金融问题,以及设计新的和创新的金融产品。

非参数统计代写

非参数统计指的是一种统计方法,其中不假设数据来自于由少数参数决定的规定模型;这种模型的例子包括正态分布模型和线性回归模型。

广义线性模型代考

广义线性模型(GLM)归属统计学领域,是一种应用灵活的线性回归模型。该模型允许因变量的偏差分布有除了正态分布之外的其它分布。

术语 广义线性模型(GLM)通常是指给定连续和/或分类预测因素的连续响应变量的常规线性回归模型。它包括多元线性回归,以及方差分析和方差分析(仅含固定效应)。

有限元方法代写

有限元方法(FEM)是一种流行的方法,用于数值解决工程和数学建模中出现的微分方程。典型的问题领域包括结构分析、传热、流体流动、质量运输和电磁势等传统领域。

有限元是一种通用的数值方法,用于解决两个或三个空间变量的偏微分方程(即一些边界值问题)。为了解决一个问题,有限元将一个大系统细分为更小、更简单的部分,称为有限元。这是通过在空间维度上的特定空间离散化来实现的,它是通过构建对象的网格来实现的:用于求解的数值域,它有有限数量的点。边界值问题的有限元方法表述最终导致一个代数方程组。该方法在域上对未知函数进行逼近。[1] 然后将模拟这些有限元的简单方程组合成一个更大的方程系统,以模拟整个问题。然后,有限元通过变化微积分使相关的误差函数最小化来逼近一个解决方案。

tatistics-lab作为专业的留学生服务机构,多年来已为美国、英国、加拿大、澳洲等留学热门地的学生提供专业的学术服务,包括但不限于Essay代写,Assignment代写,Dissertation代写,Report代写,小组作业代写,Proposal代写,Paper代写,Presentation代写,计算机作业代写,论文修改和润色,网课代做,exam代考等等。写作范围涵盖高中,本科,研究生等海外留学全阶段,辐射金融,经济学,会计学,审计学,管理学等全球99%专业科目。写作团队既有专业英语母语作者,也有海外名校硕博留学生,每位写作老师都拥有过硬的语言能力,专业的学科背景和学术写作经验。我们承诺100%原创,100%专业,100%准时,100%满意。

随机分析代写

随机微积分是数学的一个分支,对随机过程进行操作。它允许为随机过程的积分定义一个关于随机过程的一致的积分理论。这个领域是由日本数学家伊藤清在第二次世界大战期间创建并开始的。

时间序列分析代写

随机过程,是依赖于参数的一组随机变量的全体,参数通常是时间。 随机变量是随机现象的数量表现,其时间序列是一组按照时间发生先后顺序进行排列的数据点序列。通常一组时间序列的时间间隔为一恒定值(如1秒,5分钟,12小时,7天,1年),因此时间序列可以作为离散时间数据进行分析处理。研究时间序列数据的意义在于现实中,往往需要研究某个事物其随时间发展变化的规律。这就需要通过研究该事物过去发展的历史记录,以得到其自身发展的规律。

回归分析代写

多元回归分析渐进(Multiple Regression Analysis Asymptotics)属于计量经济学领域,主要是一种数学上的统计分析方法,可以分析复杂情况下各影响因素的数学关系,在自然科学、社会和经济学等多个领域内应用广泛。

MATLAB代写

MATLAB 是一种用于技术计算的高性能语言。它将计算、可视化和编程集成在一个易于使用的环境中,其中问题和解决方案以熟悉的数学符号表示。典型用途包括:数学和计算算法开发建模、仿真和原型制作数据分析、探索和可视化科学和工程图形应用程序开发,包括图形用户界面构建MATLAB 是一个交互式系统,其基本数据元素是一个不需要维度的数组。这使您可以解决许多技术计算问题,尤其是那些具有矩阵和向量公式的问题,而只需用 C 或 Fortran 等标量非交互式语言编写程序所需的时间的一小部分。MATLAB 名称代表矩阵实验室。MATLAB 最初的编写目的是提供对由 LINPACK 和 EISPACK 项目开发的矩阵软件的轻松访问,这两个项目共同代表了矩阵计算软件的最新技术。MATLAB 经过多年的发展,得到了许多用户的投入。在大学环境中,它是数学、工程和科学入门和高级课程的标准教学工具。在工业领域,MATLAB 是高效研究、开发和分析的首选工具。MATLAB 具有一系列称为工具箱的特定于应用程序的解决方案。对于大多数 MATLAB 用户来说非常重要,工具箱允许您学习和应用专业技术。工具箱是 MATLAB 函数(M 文件)的综合集合,可扩展 MATLAB 环境以解决特定类别的问题。可用工具箱的领域包括信号处理、控制系统、神经网络、模糊逻辑、小波、仿真等。