数学代写|计量经济学原理代写Principles of Econometrics代考|Estimating the Regression Parameters

如果你也在 怎样代写计量经济学Principles of Econometrics这个学科遇到相关的难题,请随时右上角联系我们的24/7代写客服。

计量经济学是以数理经济学和数理统计学为方法论基础,对于经济问题试图对理论上的数量接近和经验(实证研究)上的数量接近这两者进行综合而产生的经济学分支。

statistics-lab™ 为您的留学生涯保驾护航 在代写计量经济学Principles of Econometrics方面已经树立了自己的口碑, 保证靠谱, 高质且原创的统计Statistics代写服务。我们的专家在代写计量经济学Principles of Econometrics代写方面经验极为丰富,各种代写计量经济学Principles of Econometrics相关的作业也就用不着说。

我们提供的计量经济学Principles of Econometrics及其相关学科的代写,服务范围广, 其中包括但不限于:

- Statistical Inference 统计推断

- Statistical Computing 统计计算

- Advanced Probability Theory 高等概率论

- Advanced Mathematical Statistics 高等数理统计学

- (Generalized) Linear Models 广义线性模型

- Statistical Machine Learning 统计机器学习

- Longitudinal Data Analysis 纵向数据分析

- Foundations of Data Science 数据科学基础

数学代写|计量经济学原理代写Principles of Econometrics代考|Food Expenditure Model Data

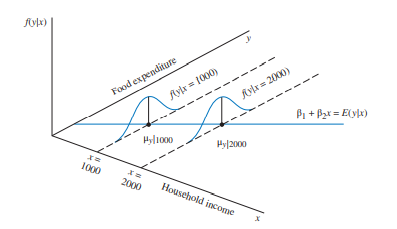

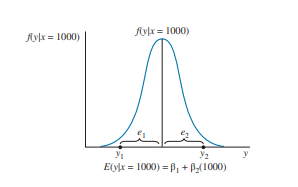

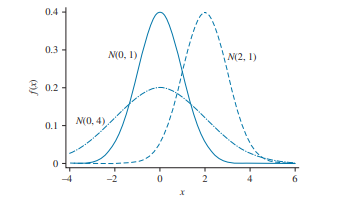

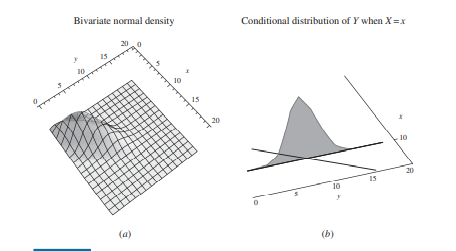

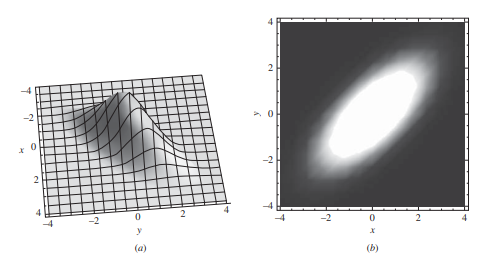

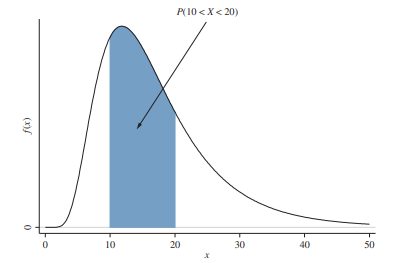

We assume that the expenditure data in Table $2.1$ satisfy the assumptions SR1-SR5. That is, we assume that the regression model $y_{i}=\beta_{1}+\beta_{2} x_{i}+e_{i}$ describes a population relationship and that the random error has conditional expected value zero. This implies that the conditional expected value of household food expenditure is a linear function of income. The conditional variance of $y$, which is the same as that of the random error $e$, is assumed constant, implying that we are equally uncertain about the relationship between $y$ and $x$ for all observations. Given $\mathbf{x}$ the values of $y$ for different households are assumed uncorrelated with each other.

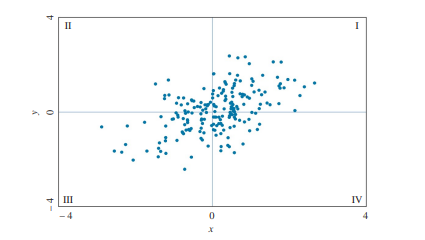

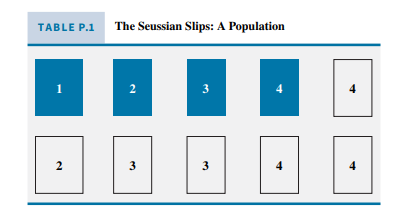

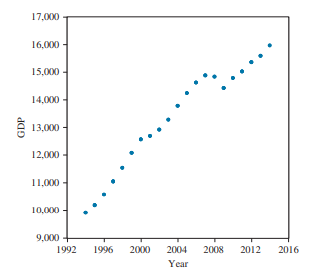

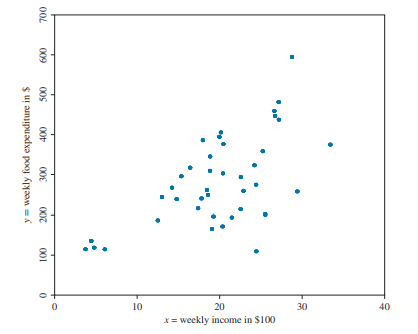

Given this theoretical model for explaining the sample observations on household food expenditure, the problem now is how to use the sample information in Table 2.1, specific values of $y_{i}$ and $x_{i}$, to estimate the unknown regression parameters $\beta_{1}$ and $\beta_{2}$. These parameters represent the unknown intercept and slope coefficients for the food expenditure-income relationship. If we represent the 40 data points as $\left(y_{i}, x_{i}\right), i=1, \ldots, N=40$, and plot them, we obtain the scatter diagram in Figure $2.6$.Our problem is to estimate the location of the mean expenditure line $E\left(y_{i} \mid \mathbf{x}\right)=\beta_{1}+\beta_{2} x_{i}$. We would expect this line to be somewhere in the middle of all the data points since it represents population mean, or average, behavior. To estimate $\beta_{1}$ and $\beta_{2}$, we could simply draw a freehand line through the middle of the data and then measure the slope and intercept with a ruler. The problem with this method is that different people would draw different lines, and the lack of a formal criterion makes it difficult to assess the accuracy of the method. Another method is to draw a line from the expenditure at the smallest income level, observation $i=1$, to the expenditure at the largest income level, $i=40$. This approach does provide a formal rule. However, it may not be a very good rule because it ignores information on the exact position of the remaining 38 observations. It would be better if we could devise a rule that uses all the information from all the data points.

数学代写|计量经济学原理代写Principles of Econometrics代考|The Expected Values of b1 and b2

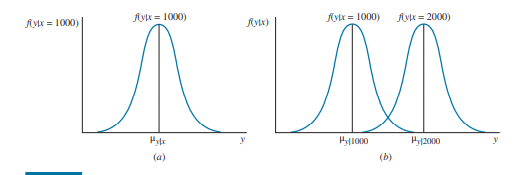

The OLS estimator $b_{2}$ is a random variable since its value is unknown until a sample is collected. What we will show is that if our model assumptions hold, then $E\left(b_{2} \mid \mathbf{x}\right)=\beta_{2}$; that is, given $\mathbf{x}$ the expected value of $b_{2}$ is equal to the true parameter $\beta_{2}$. When the expected value of any estimator of a parameter equals the true parameter value, then that estimator is unbiased. Since $E\left(b_{2} \mid \mathbf{x}\right)=\beta_{2}$, the least squares estimator $b_{2}$ given $x$ is an unbiased estimator of $\beta_{2}$. In $S$ ection $2.10$, we will show that the least squares estimator $b_{2}$ is unconditionally unbiased also, $E\left(b_{2}\right)=\beta_{2}$. The intuitive meaning of unbiasedness comes from the sampling interpretation of mathematical expectation. Recognize that one sample of size $N$ is just one of many samples that we could have been selected. If the formula for $b_{2}$ is used to estimate $\beta_{2}$ in each of those possible samples, then, if our assumptions are valid, the average value of the estimates $b_{2}$ obtained from all possible samples will be $\beta_{2}$.

We will show that this result is true so that we can illustrate the part played by the assumptions of the linear regression model. In (2.12), what parts are random? The parameter $\beta_{2}$ is not random. It is a population parameter we are trying to estimate. Conditional on $\mathbf{x}$ we can treat $x_{i}$ as if it is not random. Then, conditional on $\mathbf{x}, w_{i}$ is not random either, as it depends only on the values of $x_{i}$. The only random factors in (2.12) are the random error terms $e_{i}$. We can find the conditional expected value of $b_{2}$ using the fact that the expected value of a sum is the sum of the expected values:

$$

\begin{aligned}

E\left(b_{2} \mid \mathbf{x}\right) &=E\left(\beta_{2}+\sum w_{i} e_{i} \mid \mathbf{x}\right)=E\left(\beta_{2}+w_{1} e_{1}+w_{2} e_{2}+\cdots+w_{N} e_{N} \mid \mathbf{x}\right) \

&=E\left(\beta_{2}\right)+E\left(w_{1} e_{1} \mid \mathbf{x}\right)+E\left(w_{2} e_{2} \mid \mathbf{x}\right)+\cdots+E\left(w_{N} e_{N} \mid \mathbf{x}\right) \

&=\beta_{2}+\sum E\left(w_{i} e_{i} \mid \mathbf{x}\right) \

&=\beta_{2}+\sum w_{i} E\left(e_{i} \mid \mathbf{x}\right)=\beta_{2}

\end{aligned}

$$

The rules of expected values are fully discussed in the Probability Primer, Section P.5, and Appendix B. 1.1. In the last line of (2.13), we use two assumptions. First, $E\left(w_{i} e_{i} \mid \mathbf{x}\right)=w_{i} E\left(e_{i} \mid \mathbf{x}\right)$ because conditional on $\mathbf{x}$ the terms $w_{i}$ are not random, and constants can be factored out of expected values. Second, we have relied on the assumption that $E\left(e_{i} \mid \mathbf{x}\right)=0$. Actually, if $E\left(e_{i} \mid \mathbf{x}\right)=c$, where $c$ is any constant value, such as 3 , then $E\left(b_{2} \mid \mathbf{x}\right)=\beta_{2}$. Given $\mathbf{x}$, the OLS estimator $b_{2}$ is an unbiased estimator of the regression parameter $\beta_{2}$. On the other hand, if $E\left(e_{i} \mid \mathbf{x}\right) \neq 0$ and it depends on $\mathbf{x}$ in some way, then $b_{2}$ is a biased estimator of $\beta_{2}$. One leading case in which the assumption $E\left(e_{i} \mid \mathbf{x}\right)=0$ fails is due to omitted variables. Recall that $e_{i}$ contains everything else affecting $y_{i}$ other than $x_{i}$. If we have omitted anything that is important and that is correlated with $\mathbf{x}$ then we would expect that $E\left(e_{i} \mid \mathbf{x}\right) \neq 0$ and $E\left(b_{2} \mid \mathbf{x}\right) \neq \beta_{2}$. In Chapter 6 we discuss this omitted variables bias. Here we have shown that conditional on $\mathbf{x}$, and under SR1-SR5, the least squares estimator is linear and unbiased. In Section 2.10, we show that $E\left(b_{2}\right)=\beta_{2}$ without conditioning on $\mathbf{x}$.

The unbiasedness of the estimator $b_{2}$ is an important sampling property. On average, over all possible samples from the population, the least squares estimator is “correct,” on average, and this is one desirable property of an estimator. This statistical property by itself does not mean that $b_{2}$ is a good estimator of $\beta_{2}$, but it is part of the story. The unbiasedness property is related to what happens in all possible samples of data from the same population. The fact that $b_{2}$ is unbiased does not imply anything about what might happen in just one sample. An individual estimate (a number) $b_{2}$ may be near to, or far from, $\beta_{2}$. Since $\beta_{2}$ is never known we will never know, given

one sample, whether our estimate is “close” to $\beta_{2}$ or not. Thus, the estimate $b_{2}=10.21$ may be close to $\beta_{2}$ or not.

The least squares estimator $b_{1}$ of $\beta_{1}$ is also an unbiased estimator, and $E\left(b_{1} \mid \mathbf{x}\right)=\beta_{1}$ if the model assumptions hold.

数学代写|计量经济学原理代写Principles of Econometrics代考|Assessing the Least Squares Estimators

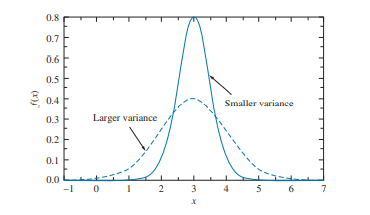

Using the food expenditure data, we have estimated the parameters of the regression model $y_{i}=\beta_{1}+\beta_{2} x_{i}+e_{i}$ using the least squares formulas in (2.7) and (2.8). We obtained the least squares estimates $b_{1}=83.42$ and $b_{2}=10.21$. It is natural, but, as we shall argue, misguided, to ask the question “How good are these estimates?” This question is not answerable. We will never know the true values of the population parameters $\beta_{1}$ or $\beta_{2}$, so we cannot say how close $b_{1}=83.42$ and $b_{2}=10.21$ are to the true values. The least squares estimates are numbers that may or may not be close to the true parameter values, and we will never know.

Rather than asking about the quality of the estimates we will take a step back and examine the quality of the least squares estimation procedure. The motivation for this approach is this: if we were to collect another sample of data, by choosing another set of 40 households to survey, we would have obtained different estimates $b_{1}$ and $b_{2}$, even if we had carefully selected households with the same incomes as in the initial sample. This sampling variation is unavoidable. Different samples will yield different estimates because household food expenditures, $y_{i}, i=1, \ldots, 40$, are random variables. Their values are not known until the sample is collected. Consequently, when viewed as an estimation procedure, $b_{1}$ and $b_{2}$ are also random variables, because their values depend on the random variable $y$. In this context, we call $b_{1}$ and $b_{2}$ the least squares estimators.

We can investigate the properties of the estimators $b_{1}$ and $b_{2}$, which are called their sampling properties, and deal with the following important questions:

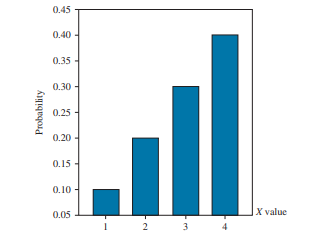

- If the least squares estimators $b_{1}$ and $b_{2}$ are random variables, then what are their expected values, variances, covariances, and probability distributions?

- The least squares principle is only one way of using the data to obtain estimates of $\beta_{1}$ and $\beta_{2}$. How do the least squares estimators compare with other procedures that might be used, and how can we compare alternative estimators? For example, is there another estimator that has a higher probability of producing an estimate that is close to $\beta_{2}$ ?

We examine these questions in two steps to make things easier. In the first step, we investigate the properties of the least squares estimators conditional on the values of the explanatory variable in the sample. That is, conditional on $\mathbf{x}$. Making the analysis conditional on $\mathbf{x}$ is equivalent to saying that, when we consider all possible samples, the household income values in the sample stay the

same from one sample to the next; only the random errors and food expenditure values change. This assumption is clearly not realistic but it simplifies the analysis. By conditioning on $\mathbf{x}$, we are holding it constant, or fixed, meaning that we can treat the $x$-values as “not random.”

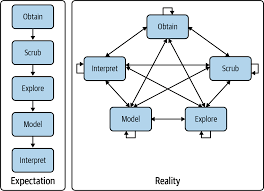

In the second step, considered in Section $2.10$, we return to the random sampling assumption and recognize that $\left(y_{i}, x_{i}\right)$ data pairs are random, and randomly selecting households from a population leads to food expenditures and incomes that are random. However, even in this case and treating $\mathbf{x}$ as random, we will discover that most of our conclusions that treated $\mathbf{x}$ as nonrandom remain the same.

In either case, whether we make the analysis conditional on $\mathbf{x}$ or make the analysis general by treating $\mathbf{x}$ as random, the answers to the questions above depend critically on whether the assumptions SR1-SR5 are satisfied. In later chapters, we will discuss how to check whether the assumptions we make hold in a specific application, and what we might do if one or more assumptions are shown not to hold.

计量经济学代考

数学代写|计量经济学原理代写Principles of Econometrics代考|Food Expenditure Model Data

我们假设表中的支出数据2.1满足假设 SR1-SR5。也就是说,我们假设回归模型是一世=b1+b2X一世+和一世描述了总体关系,并且随机误差的条件期望值为零。这意味着家庭食品支出的条件期望值是收入的线性函数。的条件方差是,与随机误差相同和, 假设为常数,这意味着我们同样不确定两者之间的关系是和X对于所有观察。给定X的值是对于不同的家庭,假设彼此不相关。

给定这个解释家庭食品支出样本观察的理论模型,现在的问题是如何使用表 2.1 中的样本信息,具体值是一世和X一世, 估计未知的回归参数b1和b2. 这些参数代表食品支出-收入关系的未知截距和斜率系数。如果我们将 40 个数据点表示为(是一世,X一世),一世=1,…,ñ=40, 并绘制它们, 我们得到了如图中的散点图2.6.我们的问题是估计平均支出线的位置和(是一世∣X)=b1+b2X一世. 我们希望这条线位于所有数据点的中间,因为它代表总体平均或平均行为。估计b1和b2,我们可以简单地在数据中间画一条手绘线,然后用尺子测量斜率和截距。这种方法的问题是不同的人会画出不同的线,而且缺乏正式的标准,很难评估方法的准确性。另一种方法是在最低收入水平的支出上画一条线,观察一世=1, 对最高收入水平的支出,一世=40. 这种方法确实提供了一个正式的规则。但是,它可能不是一个很好的规则,因为它忽略了剩余 38 个观测值的确切位置的信息。如果我们可以设计一个使用来自所有数据点的所有信息的规则会更好。

数学代写|计量经济学原理代写Principles of Econometrics代考|The Expected Values of b1 and b2

OLS 估计器b2是一个随机变量,因为在收集样本之前它的值是未知的。我们将展示的是,如果我们的模型假设成立,那么和(b2∣X)=b2; 也就是说,给定X的期望值b2等于 true 参数b2. 当参数的任何估计器的期望值等于真实参数值时,该估计器是无偏的。自从和(b2∣X)=b2, 最小二乘估计量b2给定X是一个无偏估计量b2. 在小号选举2.10,我们将证明最小二乘估计b2也是无条件无偏的,和(b2)=b2. 无偏性的直观含义来自数学期望的抽样解释。认识到一个大小的样本ñ只是我们可以选择的众多样本之一。如果公式为b2用于估计b2在每个可能的样本中,如果我们的假设是有效的,那么估计的平均值b2从所有可能的样本中获得b2.

我们将证明这个结果是正确的,以便我们可以说明线性回归模型的假设所起的作用。在(2.12)中,哪些部分是随机的?参数b2不是随机的。这是我们试图估计的人口参数。有条件的X我们可以治疗X一世好像它不是随机的。那么,有条件的X,在一世也不是随机的,因为它仅取决于X一世. (2.12) 中唯一的随机因素是随机误差项和一世. 我们可以找到条件期望值b2使用总和的期望值是期望值之和的事实:

和(b2∣X)=和(b2+∑在一世和一世∣X)=和(b2+在1和1+在2和2+⋯+在ñ和ñ∣X) =和(b2)+和(在1和1∣X)+和(在2和2∣X)+⋯+和(在ñ和ñ∣X) =b2+∑和(在一世和一世∣X) =b2+∑在一世和(和一世∣X)=b2

期望值的规则在概率入门的第 P.5 节和附录 B.1.1 中进行了充分讨论。在 (2.13) 的最后一行,我们使用了两个假设。第一的,和(在一世和一世∣X)=在一世和(和一世∣X)因为有条件X条款在一世不是随机的,并且常数可以从预期值中扣除。其次,我们依赖的假设是和(和一世∣X)=0. 实际上,如果和(和一世∣X)=C, 在哪里C是任何常数值,例如 3 ,则和(b2∣X)=b2. 给定X, OLS 估计量b2是回归参数的无偏估计量b2. 另一方面,如果和(和一世∣X)≠0这取决于X以某种方式,那么b2是一个有偏估计量b2. 一个主要案例,其中假设和(和一世∣X)=0失败是由于省略了变量。回顾和一世包含所有其他影响是一世以外X一世. 如果我们省略了任何重要且与X那么我们会期望和(和一世∣X)≠0和和(b2∣X)≠b2. 在第 6 章中,我们讨论了这种遗漏变量偏差。在这里,我们已经证明了X,并且在 SR1-SR5 下,最小二乘估计量是线性且无偏的。在 2.10 节中,我们证明了和(b2)=b2无需调节X.

估计量的无偏性b2是一个重要的采样属性。平均而言,在总体的所有可能样本中,最小二乘估计量平均而言是“正确的”,这是估计量的一个理想属性。这种统计特性本身并不意味着b2是一个很好的估计b2,但这是故事的一部分。无偏性与来自同一总体的所有可能数据样本中发生的情况有关。事实是b2不偏不倚并不意味着仅在一个样本中可能发生的事情。个人估计(数字)b2可能接近或远离,b2. 自从b2永远不知道,我们永远不会知道,给定

一个样本,我们的估计是否“接近”b2或不。因此,估计b2=10.21可能接近b2或不。

最小二乘估计器b1的b1也是一个无偏估计量,并且和(b1∣X)=b1如果模型假设成立。

数学代写|计量经济学原理代写Principles of Econometrics代考|Assessing the Least Squares Estimators

使用食品支出数据,我们估计了回归模型的参数是一世=b1+b2X一世+和一世使用 (2.7) 和 (2.8) 中的最小二乘公式。我们获得了最小二乘估计b1=83.42和b2=10.21. 提出“这些估计值有多好”这个问题是很自然的,但正如我们将要论证的那样,这是被误导的。这个问题无法回答。我们永远不会知道总体参数的真实值b1或者b2,所以我们不能说有多接近b1=83.42和b2=10.21是真实的价值。最小二乘估计是可能接近也可能不接近真实参数值的数字,我们永远不会知道。

与其询问估计的质量,我们将退后一步,检查最小二乘估计程序的质量。这种方法的动机是:如果我们要收集另一个数据样本,通过选择另一组 40 个家庭进行调查,我们会得到不同的估计b1和b2,即使我们仔细选择了与初始样本中收入相同的家庭。这种抽样变化是不可避免的。不同的样本会产生不同的估计值,因为家庭食品支出、是一世,一世=1,…,40, 是随机变量。在收集样本之前,它们的值是未知的。因此,当被视为一种估计程序时,b1和b2也是随机变量,因为它们的值取决于随机变量是. 在这种情况下,我们称b1和b2最小二乘估计量。

我们可以研究估计器的性质b1和b2,称为它们的采样属性,并处理以下重要问题:

- 如果最小二乘估计b1和b2是随机变量,那么它们的期望值、方差、协方差和概率分布是什么?

- 最小二乘原理只是使用数据获得估计值的一种方法b1和b2. 最小二乘估计器如何与可能使用的其他程序进行比较,我们如何比较替代估计器?例如,是否有另一个估计器有更高的概率产生接近于b2 ?

我们分两个步骤检查这些问题,以使事情变得更容易。第一步,我们研究最小二乘估计量的性质,条件是样本中解释变量的值。也就是说,有条件的X. 以分析为条件X相当于说,当我们考虑所有可能的样本时,样本中的家庭收入值保持在

从一个样本到下一个样本都是一样的;只有随机误差和食品支出值发生变化。这个假设显然是不现实的,但它简化了分析。通过调节X,我们将其保持不变或固定,这意味着我们可以将X-值“非随机”。

第二步,在章节中考虑2.10,我们回到随机抽样假设并认识到(是一世,X一世)数据对是随机的,从人口中随机选择家庭会导致食品支出和收入是随机的。然而,即使在这种情况下和治疗X作为随机的,我们会发现我们的大部分结论X因为非随机保持不变。

在任何一种情况下,我们是否使分析以X或通过处理使分析一般化X作为随机的,上述问题的答案主要取决于假设 SR1-SR5 是否得到满足。在后面的章节中,我们将讨论如何检查我们所做的假设在特定应用中是否成立,以及如果一个或多个假设被证明不成立,我们可能会做什么。

统计代写请认准statistics-lab™. statistics-lab™为您的留学生涯保驾护航。

金融工程代写

金融工程是使用数学技术来解决金融问题。金融工程使用计算机科学、统计学、经济学和应用数学领域的工具和知识来解决当前的金融问题,以及设计新的和创新的金融产品。

非参数统计代写

非参数统计指的是一种统计方法,其中不假设数据来自于由少数参数决定的规定模型;这种模型的例子包括正态分布模型和线性回归模型。

广义线性模型代考

广义线性模型(GLM)归属统计学领域,是一种应用灵活的线性回归模型。该模型允许因变量的偏差分布有除了正态分布之外的其它分布。

术语 广义线性模型(GLM)通常是指给定连续和/或分类预测因素的连续响应变量的常规线性回归模型。它包括多元线性回归,以及方差分析和方差分析(仅含固定效应)。

有限元方法代写

有限元方法(FEM)是一种流行的方法,用于数值解决工程和数学建模中出现的微分方程。典型的问题领域包括结构分析、传热、流体流动、质量运输和电磁势等传统领域。

有限元是一种通用的数值方法,用于解决两个或三个空间变量的偏微分方程(即一些边界值问题)。为了解决一个问题,有限元将一个大系统细分为更小、更简单的部分,称为有限元。这是通过在空间维度上的特定空间离散化来实现的,它是通过构建对象的网格来实现的:用于求解的数值域,它有有限数量的点。边界值问题的有限元方法表述最终导致一个代数方程组。该方法在域上对未知函数进行逼近。[1] 然后将模拟这些有限元的简单方程组合成一个更大的方程系统,以模拟整个问题。然后,有限元通过变化微积分使相关的误差函数最小化来逼近一个解决方案。

tatistics-lab作为专业的留学生服务机构,多年来已为美国、英国、加拿大、澳洲等留学热门地的学生提供专业的学术服务,包括但不限于Essay代写,Assignment代写,Dissertation代写,Report代写,小组作业代写,Proposal代写,Paper代写,Presentation代写,计算机作业代写,论文修改和润色,网课代做,exam代考等等。写作范围涵盖高中,本科,研究生等海外留学全阶段,辐射金融,经济学,会计学,审计学,管理学等全球99%专业科目。写作团队既有专业英语母语作者,也有海外名校硕博留学生,每位写作老师都拥有过硬的语言能力,专业的学科背景和学术写作经验。我们承诺100%原创,100%专业,100%准时,100%满意。

随机分析代写

随机微积分是数学的一个分支,对随机过程进行操作。它允许为随机过程的积分定义一个关于随机过程的一致的积分理论。这个领域是由日本数学家伊藤清在第二次世界大战期间创建并开始的。

时间序列分析代写

随机过程,是依赖于参数的一组随机变量的全体,参数通常是时间。 随机变量是随机现象的数量表现,其时间序列是一组按照时间发生先后顺序进行排列的数据点序列。通常一组时间序列的时间间隔为一恒定值(如1秒,5分钟,12小时,7天,1年),因此时间序列可以作为离散时间数据进行分析处理。研究时间序列数据的意义在于现实中,往往需要研究某个事物其随时间发展变化的规律。这就需要通过研究该事物过去发展的历史记录,以得到其自身发展的规律。

回归分析代写

多元回归分析渐进(Multiple Regression Analysis Asymptotics)属于计量经济学领域,主要是一种数学上的统计分析方法,可以分析复杂情况下各影响因素的数学关系,在自然科学、社会和经济学等多个领域内应用广泛。

MATLAB代写

MATLAB 是一种用于技术计算的高性能语言。它将计算、可视化和编程集成在一个易于使用的环境中,其中问题和解决方案以熟悉的数学符号表示。典型用途包括:数学和计算算法开发建模、仿真和原型制作数据分析、探索和可视化科学和工程图形应用程序开发,包括图形用户界面构建MATLAB 是一个交互式系统,其基本数据元素是一个不需要维度的数组。这使您可以解决许多技术计算问题,尤其是那些具有矩阵和向量公式的问题,而只需用 C 或 Fortran 等标量非交互式语言编写程序所需的时间的一小部分。MATLAB 名称代表矩阵实验室。MATLAB 最初的编写目的是提供对由 LINPACK 和 EISPACK 项目开发的矩阵软件的轻松访问,这两个项目共同代表了矩阵计算软件的最新技术。MATLAB 经过多年的发展,得到了许多用户的投入。在大学环境中,它是数学、工程和科学入门和高级课程的标准教学工具。在工业领域,MATLAB 是高效研究、开发和分析的首选工具。MATLAB 具有一系列称为工具箱的特定于应用程序的解决方案。对于大多数 MATLAB 用户来说非常重要,工具箱允许您学习和应用专业技术。工具箱是 MATLAB 函数(M 文件)的综合集合,可扩展 MATLAB 环境以解决特定类别的问题。可用工具箱的领域包括信号处理、控制系统、神经网络、模糊逻辑、小波、仿真等。