经济代写|计量经济学作业代写Econometrics代考|The Algebra of Least Squares

如果你也在 怎样代写计量经济学Econometrics这个学科遇到相关的难题,请随时右上角联系我们的24/7代写客服。

计量经济学,对经济关系的统计和数学分析,通常作为经济预测的基础。这些信息有时被政府用来制定经济政策,也被私人企业用来帮助价格、库存和生产方面的决策。

statistics-lab™ 为您的留学生涯保驾护航 在代写计量经济学Econometrics方面已经树立了自己的口碑, 保证靠谱, 高质且原创的统计Statistics代写服务。我们的专家在代写计量经济学Econometrics代写方面经验极为丰富,各种代写计量经济学Econometrics相关的作业也就用不着说。

我们提供的计量经济学Econometrics及其相关学科的代写,服务范围广, 其中包括但不限于:

- Statistical Inference 统计推断

- Statistical Computing 统计计算

- Advanced Probability Theory 高等概率论

- Advanced Mathematical Statistics 高等数理统计学

- (Generalized) Linear Models 广义线性模型

- Statistical Machine Learning 统计机器学习

- Longitudinal Data Analysis 纵向数据分析

- Foundations of Data Science 数据科学基础

经济代写|计量经济学作业代写Econometrics代考|Samples

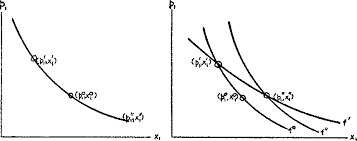

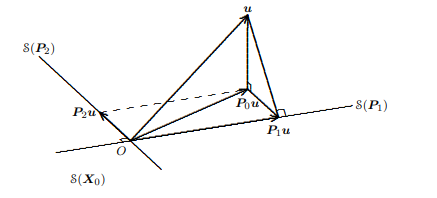

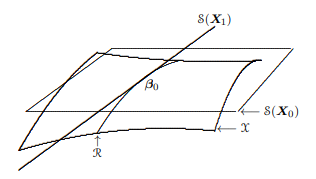

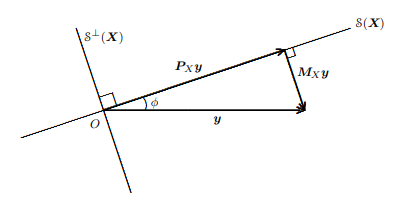

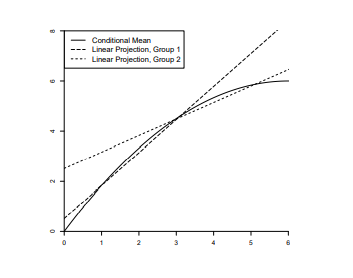

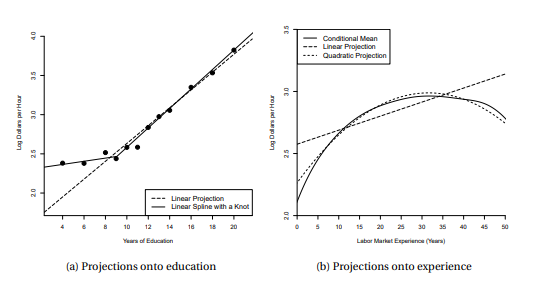

In Section $2.18$ we derived and discussed the best linear predictor of $y$ given $x$ for a pair of random variables $(y, \boldsymbol{x}) \in \mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{R}^{k}$ and called this the linear projection model. We are now interested in estimating the parameters of this model, in particular the projection coefficient

$$

\boldsymbol{\beta}=\left(\mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{x} \boldsymbol{x}^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{x} y]

$$

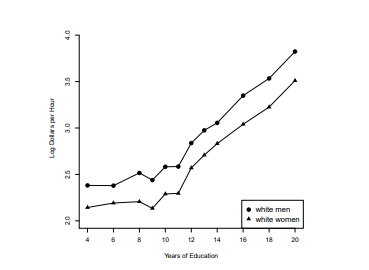

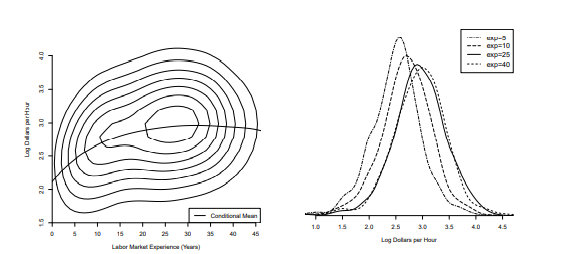

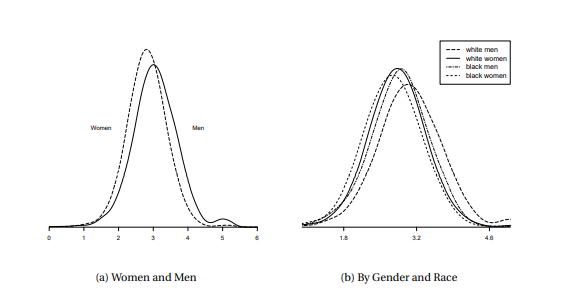

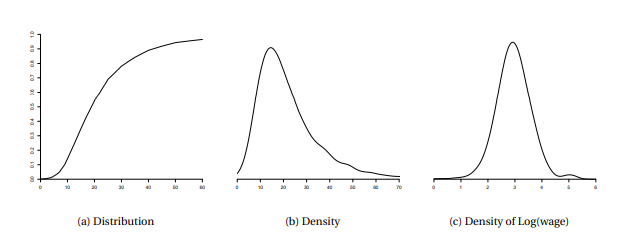

We can estimate $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ from observational data which includes joint measurements on the variables $(y, x)$. For example, supposing we are interested in estimating a wage equation, we would use a dataset with observations on wages (or weekly earnings), education, experience (or age), and demographic characteristics (gender, race, location). One possible dataset is the Current Population Survey (CPS), a survey of U.S. households which includes questions on employment, income, education, and demographic characteristics.

Notationally we wish to distinguish observations from the underlying random variables. The convention in econometrics is to denote observations by appending a subscript $i$ which runs from 1 to $n$, thus the $i^{t h}$ observation is $\left(y_{i}, \boldsymbol{x}{i}\right)$, and $n$ denotes the sample size. The dataset is then $\left{\left(y{i}, \boldsymbol{x}_{i}\right) ; i=1, \ldots, n\right}$. We call this the sample or the observations.

From the viewpoint of empirical analysis a dataset is an array of numbers often organized as a table, where the columns of the table correspond to distinct variables and the rows correspond to distinct observations. For empirical analysis the dataset and observations are fixed in the sense that they are numbers presented to the researcher. For statistical analysis we need to view the dataset as random, or more precisely as a realization of a random process.

In order for the coefficient $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ defined in (3.1) to make sense as defined the expectations over the random variables $(\boldsymbol{x}, y)$ need to be common across the observations. The most elegant approach to ensure this is to assume that the observations are draws from an identical underlying population $F$. This is the standard assumption that the observations are identically distributed:

This assumption does not need to be viewed as literally true, rather it is a useful modeling device so that parameters such as $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ are well defined. This assumption should be interpreted as how we view an observation a priori, before we actually observe it. If I tell you that we have a sample with $n=59$ observations set in no particular order, then it makes sense to view two observations, say 17 and 58 , as draws from the same distribution. We have no reason to expect anything special about either observation.

In econometric theory we refer to the underlying common distribution $F$ as the population. Some authors prefer the label the data-generating-process (DGP). You can think of it as a theoretical concept or an infinitely-large potential population. In contrast we refer to the observations available to us $\left{\left(y_{i}, x_{i}\right): i=1, \ldots, n\right}$ as the sample or dataset. In some contexts the dataset consists of all potential observations, for example administrative tax records may contain every single taxpayer in a political unit. Even in this case we view the observations as if they are random draws from an underlying infinitely-large population as this will allow us to apply the tools of statistical theory.

The linear projection model applies to the random observations $\left(y_{i}, \boldsymbol{x}{l}\right)$. This means that the probability model for the observations is the same as that described in Section $2.18$. We can write the model as $$ y{i}=\boldsymbol{x}{i}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\beta}+e{i}

$$

where the linear projection coefficient $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ is defined as

$$

\boldsymbol{\beta}=\underset{b \in \mathbb{R}^{k}}{\operatorname{argmin}} S(\boldsymbol{b}),

$$

the minimizer of the expected squared error

$$

S(\boldsymbol{\beta})=\mathbb{E}\left[\left(y_{i}-\boldsymbol{x}{i}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\beta}\right)^{2}\right] $$ The coefficient has the explicit solution $$ \boldsymbol{\beta}=\left(\mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{x}{i} \boldsymbol{x}{i}^{\prime}\right]\right)^{-1} \mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{x}{i} y_{i}\right]

$$

经济代写|计量经济学作业代写Econometrics代考|Moment Estimators

We want tn estimate the cnefficient $\beta$ defined in (3.5) from the sample of nhservatinns. Nntice that $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ is written as a function of certain population expectations. In this context an appropriate estimator is the same function of the sample moments. Let’s explain this in detail.

To start, suppose that we are interested in the population mean $\mu$ of a random variable $y_{i}$ with dis= tribution function $F$

$$

\mu=\mathbb{E}\left[y_{i}\right]=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} y d F(y)

$$

The mean $\mu$ is a function of the distribution $F$ as written in (3.6). To estimate $\mu$ given a sample $\left{y_{1}, \ldots, y_{n}\right}$ a natural estimator is the sample mean

$$

\widehat{\jmath}=\bar{y}=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} y_{i} .

$$

Notice that we have written this using two pieces of notation. The notation $\bar{y}$ with the bar on top is conventional for a sample mean. The notation $\hat{\mu}$ with the hat ” $\wedge$ ” is conventional in econometrics to

denote an estimator of the parameter $\mu$. In this case $\bar{y}$ is the estimator of $\mu$, so $\widehat{\mu}$ and $\bar{y}$ are the same. The sample mean $\bar{y}$ can be viewed as the natural analog of the population mean (3.6) because $\bar{y}$ equals the expectation (3.6) with respect to the empirical distribution – the discrete distribution which puts weight $1 / n$ on each observation $y_{i}$. There are many other justifications for $\bar{y}$ as an estimator for $\mu$. We will defer these discussions for now. Suffice it to say that it is the conventional estimator in the lack of other information about $\mu$ or the distribution of $y_{i}$.

Now suppose that we are interested in a set of population means of possibly non-linear functions of a random vector $\boldsymbol{y}$, say $\boldsymbol{\mu}=\mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{h}\left(\boldsymbol{y}{i}\right)\right]$. For example, we may be interested in the first two moments of $y{i}$, $\mathbb{E}\left[y_{i}\right]$ and $\mathbb{E}\left[y_{i}^{2}\right]$. In this case the natural estimator is the vector of sample means,

$$

\widehat{\boldsymbol{\mu}}=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \boldsymbol{h}\left(y_{i}\right)

$$

where $\boldsymbol{h}(y)=\left(y, y^{2}\right)$. In this case $\widehat{\mu}{1}=\frac{1}{n} \sum{i=1}^{n} y_{i}$ and $\widehat{\mu}{2}=\frac{1}{n} \sum{i=1}^{n} y_{i}^{2}$. We call $\hat{\boldsymbol{\mu}}$ the moment estimator for $\boldsymbol{\mu}$.

Now suppose that we are interested in a nonlinear function of a set of moments. For example, consider the variance of $y$

$$

\sigma^{2}=\operatorname{var}\left[y_{i}\right]=\mathbb{E}\left[y_{i}^{2}\right]-\left(\mathbb{E}\left[y_{i}\right]\right)^{2} .

$$

In general, many parameters of interest can be written as a function of moments of $\boldsymbol{y}$. Notationally,

$$

\begin{aligned}

&\boldsymbol{\beta}=\boldsymbol{g}(\boldsymbol{\mu}) \

&\boldsymbol{\mu}=\mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{h}\left(\boldsymbol{y}{i}\right)\right] \end{aligned} $$ Here, $\boldsymbol{y}{i}$ are the random variables, $\boldsymbol{h}\left(\boldsymbol{y}{i}\right)$ are functions (transformations) of the random variables, and $\boldsymbol{\mu}$ is the mean (expectation) of these functions. $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ is the parameter of interest, and is the (nonlinear) function $\boldsymbol{g}(\cdot)$ of these means. In this context a natural estimator of $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ is obtained by replacing $\boldsymbol{\mu}$ with $\hat{\boldsymbol{\mu}}$. $$ \begin{aligned} &\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}=\boldsymbol{g}(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\mu}}) \ &\widehat{\boldsymbol{\mu}}=\frac{1}{n} \sum{i=1}^{n} \boldsymbol{h}\left(\boldsymbol{y}{i}\right) . \end{aligned} $$ The estimator $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}$ is sometimes called a “plug-in” estimator, and sometimes a “substitution” estimator. We typically call $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}$ a moment, or moment-based, estimator of $\boldsymbol{\beta}$, since it is a natural extension of the moment estimator $\hat{\boldsymbol{\mu}}$. Take the example of the variance $\sigma^{2}=\operatorname{var}\left[y{i}\right]$. Its moment estimator is

$$

\widehat{\sigma}^{2}=\widehat{\mu}{2}-\widehat{\mu}{1}^{2}=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} y_{i}^{2}-\left(\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} y_{i}\right)^{2} .

$$

This is not the only possible estimator for $\sigma^{2}$ (there is also the well-known bias-corrected estimator) but $\widehat{\sigma}^{2}$ is a straightforward and simple choice.

经济代写|计量经济学作业代写Econometrics代考|Least Squares Estimator

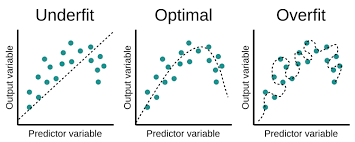

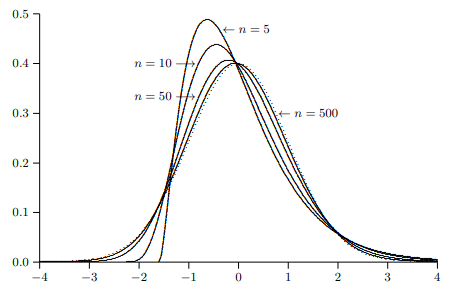

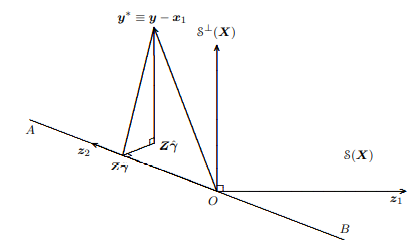

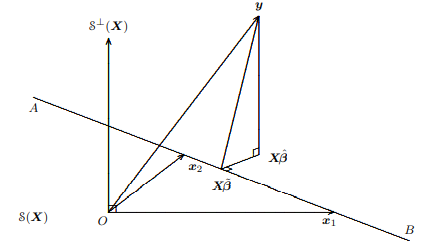

The linear projectinn coefficient $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ is defined in (3.3) as the minimizer nf the experted squared errno $S(\overline{\boldsymbol{\beta}})$ defined in (3.4). For given $\overline{\boldsymbol{\beta}}$, the expected squared error is the expectation of the squared error

$\left(y_{i}-\boldsymbol{x}{i}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\beta}\right)^{2}$. The moment estimator of $S(\boldsymbol{\beta})$ is the sample average: $$ \begin{aligned} \widehat{S}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) &=\frac{1}{n} \sum{i=1}^{n}\left(y_{i}-\boldsymbol{x}{i}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\beta}\right)^{2} \ &=\frac{1}{n} \operatorname{SSE}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) \end{aligned} $$ where $$ \operatorname{SSE}(\boldsymbol{\beta})=\sum{i=1}^{n}\left(y_{i}-\boldsymbol{x}{i}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\beta}\right)^{2} $$ is called the sum-of-squared-errors function. Since $\widehat{S}(\boldsymbol{\beta})$ is a sample average we can interpret it as an estimator of the expected squared error $S(\boldsymbol{\beta})$. Examining $\widehat{S}(\boldsymbol{\beta})$ as a function of $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ is informative about how $S(\boldsymbol{\beta})$ varies with $\boldsymbol{\beta}$. Since the projection coefficient minimizes $S(\boldsymbol{\beta})$ an analog estimator minimizes (3.7). We define the estimator $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}$ as the minimizer of $\widehat{S}(\boldsymbol{\beta})$. Definition 3.1 The least-squares estimator $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}$ is $$ \begin{gathered} \widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}=\underset{\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta} \in \widehat{R}^{l}}}{\operatorname{argmin}} \widehat{S}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) \ \boldsymbol{\beta})=\frac{1}{n} \sum{i=1}^{n}\left(y_{l}-\mathbf{x}{i}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\beta}\right)^{2} \end{gathered} $$ where $$ \widehat{\boldsymbol{\delta}}(\boldsymbol{\beta})=\frac{1}{n} \sum{l=1}^{n}\left(y_{i}-\boldsymbol{x}{l}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\beta}\right)^{2} $$ As $\widehat{S}(\boldsymbol{\beta})$ is a scale multiple of $\operatorname{SSE}(\boldsymbol{\beta})$ we may equivalently define $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}$ as the minimizer of $S S E(\boldsymbol{\beta})$ ). Hence $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}$ is commonly called the least-squares (LS) estimator of $\boldsymbol{\beta}$. The estimator is also commonly refered to as the ordinary least-squares (OLS) estimator. For the origin of this label see the historical discussion on Adrien-Marie Legendre below. Here, as is common in econometrics, we put a hat ” $\wedge$ ” over the parameter $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ to indicate that $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}$ is a sample estimate of $\boldsymbol{\beta}$. This is a helpful convention. Just by seeing the symbol $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}$ we can immediately interpret it as an estimator (because of the hat) of the parameter $\boldsymbol{\beta}$. Sometimes when we want to be explicit about the estimation method, we will write $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}{\text {ols }}$ to signify that it is the OLLS estimator. It is also common to see the notation $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{n}$, where the subscript ” $n$ ” indicates that the estimator depends on the sample size $n$.

It is important to understand the distinction between population parameters such as $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ and sample estimators such as $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}$. The population parameter $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ is a non-random feature of the population while the sample estimator $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}$ is a random feature of a random sample. $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ is fixed, while $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}$ varies across samples.

计量经济学代写

经济代写|计量经济学作业代写Econometrics代考|Samples

在部分2.18我们推导出并讨论了是给定X对于一对随机变量(是,X)∈R×Rķ并将其称为线性投影模型。我们现在对估计这个模型的参数感兴趣,特别是投影系数

b=(和[XX′])−1和[X是]

我们可以估计b来自观测数据,其中包括对变量的联合测量(是,X). 例如,假设我们有兴趣估计工资方程,我们将使用一个数据集,其中包含工资(或每周收入)、教育、经验(或年龄)和人口特征(性别、种族、位置)的观察结果。一个可能的数据集是当前人口调查 (CPS),这是一项针对美国家庭的调查,其中包括有关就业、收入、教育和人口特征的问题。

从符号上讲,我们希望将观察结果与潜在的随机变量区分开来。计量经济学的惯例是通过附加下标来表示观察结果一世从 1 到n, 就这样一世吨H观察是(是一世,X一世), 和n表示样本量。那么数据集就是\left{\left(y{i}, \boldsymbol{x}_{i}\right) ; i=1, \ldots, n\right}\left{\left(y{i}, \boldsymbol{x}_{i}\right) ; i=1, \ldots, n\right}. 我们称之为样本或观察。

从经验分析的角度来看,数据集是通常组织为表格的数字数组,其中表格的列对应于不同的变量,而行对应于不同的观察结果。对于经验分析,数据集和观察结果是固定的,因为它们是呈现给研究人员的数字。对于统计分析,我们需要将数据集视为随机的,或者更准确地说是随机过程的实现。

为了系数b在(3.1)中定义的意义在于定义对随机变量的期望(X,是)需要在观察中是共同的。确保这一点的最优雅的方法是假设观察结果来自相同的潜在人群F. 这是观测值同分布的标准假设:

这个假设不需要被视为字面上的真实,而是一个有用的建模设备,因此参数如b定义明确。这个假设应该被解释为我们在实际观察之前如何先验地看待观察。如果我告诉你我们有一个样品n=59没有特定顺序的观察值,那么查看两个观察值(例如 17 和 58 )是有意义的,因为它们来自相同的分布。我们没有理由期待这两种观察有什么特别之处。

在计量经济学理论中,我们指的是潜在的共同分布F作为人口。一些作者更喜欢数据生成过程 (DGP) 的标签。您可以将其视为一个理论概念或无限大的潜在人口。相反,我们指的是我们可用的观察结果\left{\left(y_{i}, x_{i}\right): i=1, \ldots, n\right}\left{\left(y_{i}, x_{i}\right): i=1, \ldots, n\right}作为样本或数据集。在某些情况下,数据集包含所有潜在的观察结果,例如行政税务记录可能包含政治单位中的每个纳税人。即使在这种情况下,我们也将观察结果视为从潜在的无限大群体中随机抽取,因为这将使我们能够应用统计理论的工具。

线性投影模型适用于随机观测(是一世,Xl). 这意味着观察的概率模型与第 1 节中描述的相同2.18. 我们可以将模型写为是一世=X一世′b+和一世

其中线性投影系数b定义为

b=精氨酸b∈Rķ小号(b),

期望平方误差的最小值

小号(b)=和[(是一世−X一世′b)2]系数有显式解b=(和[X一世X一世′])−1和[X一世是一世]

经济代写|计量经济学作业代写Econometrics代考|Moment Estimators

我们要 tn 估计 cnefficientb从 nhservatinns 样本中定义在 (3.5) 中。注意到b被写成某些人口预期的函数。在这种情况下,适当的估计器是样本矩的相同函数。让我们详细解释一下。

首先,假设我们对总体均值感兴趣μ随机变量是一世带分布函数F

μ=和[是一世]=∫−∞∞是dF(是)

均值μ是分布的函数F如(3.6)中所写。估计μ给定一个样本\left{y_{1}, \ldots, y_{n}\right}\left{y_{1}, \ldots, y_{n}\right}自然估计量是样本均值

Ÿ^=是¯=1n∑一世=1n是一世.

请注意,我们使用两种符号来编写它。符号是¯顶部的条形图对于样本均值来说是常规的。符号μ^带着帽子”∧” 在计量经济学中是传统的

表示参数的估计量μ. 在这种情况下是¯是的估计量μ, 所以μ^和是¯是相同的。样本均值是¯可以看作是总体均值 (3.6) 的自然类似物,因为是¯等于关于经验分布的期望(3.6)——赋予权重的离散分布1/n在每次观察是一世. 还有很多其他的理由是¯作为估计器μ. 我们将暂时推迟这些讨论。可以说它是缺乏其他信息的传统估计量μ或分布是一世.

现在假设我们对随机向量的可能非线性函数的一组总体均值感兴趣是, 说μ=和[H(是一世)]. 例如,我们可能对前两个时刻感兴趣是一世, 和[是一世]和和[是一世2]. 在这种情况下,自然估计量是样本均值的向量,

μ^=1n∑一世=1nH(是一世)

在哪里H(是)=(是,是2). 在这种情况下μ^1=1n∑一世=1n是一世和μ^2=1n∑一世=1n是一世2. 我们称之为μ^矩估计器μ.

现在假设我们对一组矩的非线性函数感兴趣。例如,考虑方差是

σ2=曾是[是一世]=和[是一世2]−(和[是一世])2.

通常,许多感兴趣的参数可以写成矩的函数是. 从符号上讲,

b=G(μ) μ=和[H(是一世)]这里,是一世是随机变量,H(是一世)是随机变量的函数(变换),并且μ是这些函数的平均值(期望值)。b是感兴趣的参数,并且是(非线性)函数G(⋅)这些手段中。在这种情况下,自然估计b通过替换获得μ和μ^.b^=G(μ^) μ^=1n∑一世=1nH(是一世).估算器b^有时称为“插件”估计器,有时称为“替代”估计器。我们通常称b^矩或基于矩的估计量b, 因为它是矩估计量的自然延伸μ^. 以方差为例σ2=曾是[是一世]. 它的矩估计量是

σ^2=μ^2−μ^12=1n∑一世=1n是一世2−(1n∑一世=1n是一世)2.

这不是唯一可能的估计量σ2(还有著名的偏差校正估计器)但是σ^2是一个简单明了的选择。

经济代写|计量经济学作业代写Econometrics代考|Least Squares Estimator

线性投影系数b在 (3.3) 中定义为最小化 nf 专家平方 errno小号(b¯)在 (3.4) 中定义。对于给定的b¯,期望平方误差是平方误差的期望

(是一世−X一世′b)2. 矩估计器小号(b)是样本平均值:小号^(b)=1n∑一世=1n(是一世−X一世′b)2 =1n上证所(b)在哪里上证所(b)=∑一世=1n(是一世−X一世′b)2称为误差平方和函数。自从小号^(b)是一个样本平均值,我们可以将其解释为预期平方误差的估计值小号(b). 检查小号^(b)作为一个函数b提供有关如何的信息小号(b)随b. 由于投影系数最小化小号(b)模拟估计器最小化(3.7)。我们定义估计器b^作为最小化器小号^(b). 定义 3.1 最小二乘估计器b^是b^=精氨酸b∈R^l^小号^(b) b)=1n∑一世=1n(是l−X一世′b)2在哪里d^(b)=1n∑l=1n(是一世−Xl′b)2作为小号^(b)是比例倍数上证所(b)我们可以等价地定义b^作为最小化器小号小号和(b))。因此b^通常称为最小二乘 (LS) 估计量b. 估计器通常也称为普通最小二乘 (OLS) 估计器。有关此标签的起源,请参见下面关于 Adrien-Marie Legendre 的历史讨论。在这里,正如计量经济学中常见的那样,我们戴上帽子”∧”过参数b表示b^是一个样本估计b. 这是一个有用的约定。只看符号b^我们可以立即将其解释为参数的估计量(因为帽子)b. 有时当我们想明确估计方法时,我们会写b^奥尔斯 表示它是 OLLS 估计量。看到符号也很常见b^n, 其中下标 ”n” 表示估计量取决于样本量n.

了解人口参数之间的区别很重要,例如b和样本估计器,例如b^. 人口参数b是总体的非随机特征,而样本估计量b^是随机样本的随机特征。b是固定的,而b^因样本而异。

统计代写请认准statistics-lab™. statistics-lab™为您的留学生涯保驾护航。

金融工程代写

金融工程是使用数学技术来解决金融问题。金融工程使用计算机科学、统计学、经济学和应用数学领域的工具和知识来解决当前的金融问题,以及设计新的和创新的金融产品。

非参数统计代写

非参数统计指的是一种统计方法,其中不假设数据来自于由少数参数决定的规定模型;这种模型的例子包括正态分布模型和线性回归模型。

广义线性模型代考

广义线性模型(GLM)归属统计学领域,是一种应用灵活的线性回归模型。该模型允许因变量的偏差分布有除了正态分布之外的其它分布。

术语 广义线性模型(GLM)通常是指给定连续和/或分类预测因素的连续响应变量的常规线性回归模型。它包括多元线性回归,以及方差分析和方差分析(仅含固定效应)。

有限元方法代写

有限元方法(FEM)是一种流行的方法,用于数值解决工程和数学建模中出现的微分方程。典型的问题领域包括结构分析、传热、流体流动、质量运输和电磁势等传统领域。

有限元是一种通用的数值方法,用于解决两个或三个空间变量的偏微分方程(即一些边界值问题)。为了解决一个问题,有限元将一个大系统细分为更小、更简单的部分,称为有限元。这是通过在空间维度上的特定空间离散化来实现的,它是通过构建对象的网格来实现的:用于求解的数值域,它有有限数量的点。边界值问题的有限元方法表述最终导致一个代数方程组。该方法在域上对未知函数进行逼近。[1] 然后将模拟这些有限元的简单方程组合成一个更大的方程系统,以模拟整个问题。然后,有限元通过变化微积分使相关的误差函数最小化来逼近一个解决方案。

tatistics-lab作为专业的留学生服务机构,多年来已为美国、英国、加拿大、澳洲等留学热门地的学生提供专业的学术服务,包括但不限于Essay代写,Assignment代写,Dissertation代写,Report代写,小组作业代写,Proposal代写,Paper代写,Presentation代写,计算机作业代写,论文修改和润色,网课代做,exam代考等等。写作范围涵盖高中,本科,研究生等海外留学全阶段,辐射金融,经济学,会计学,审计学,管理学等全球99%专业科目。写作团队既有专业英语母语作者,也有海外名校硕博留学生,每位写作老师都拥有过硬的语言能力,专业的学科背景和学术写作经验。我们承诺100%原创,100%专业,100%准时,100%满意。

随机分析代写

随机微积分是数学的一个分支,对随机过程进行操作。它允许为随机过程的积分定义一个关于随机过程的一致的积分理论。这个领域是由日本数学家伊藤清在第二次世界大战期间创建并开始的。

时间序列分析代写

随机过程,是依赖于参数的一组随机变量的全体,参数通常是时间。 随机变量是随机现象的数量表现,其时间序列是一组按照时间发生先后顺序进行排列的数据点序列。通常一组时间序列的时间间隔为一恒定值(如1秒,5分钟,12小时,7天,1年),因此时间序列可以作为离散时间数据进行分析处理。研究时间序列数据的意义在于现实中,往往需要研究某个事物其随时间发展变化的规律。这就需要通过研究该事物过去发展的历史记录,以得到其自身发展的规律。

回归分析代写

多元回归分析渐进(Multiple Regression Analysis Asymptotics)属于计量经济学领域,主要是一种数学上的统计分析方法,可以分析复杂情况下各影响因素的数学关系,在自然科学、社会和经济学等多个领域内应用广泛。

MATLAB代写

MATLAB 是一种用于技术计算的高性能语言。它将计算、可视化和编程集成在一个易于使用的环境中,其中问题和解决方案以熟悉的数学符号表示。典型用途包括:数学和计算算法开发建模、仿真和原型制作数据分析、探索和可视化科学和工程图形应用程序开发,包括图形用户界面构建MATLAB 是一个交互式系统,其基本数据元素是一个不需要维度的数组。这使您可以解决许多技术计算问题,尤其是那些具有矩阵和向量公式的问题,而只需用 C 或 Fortran 等标量非交互式语言编写程序所需的时间的一小部分。MATLAB 名称代表矩阵实验室。MATLAB 最初的编写目的是提供对由 LINPACK 和 EISPACK 项目开发的矩阵软件的轻松访问,这两个项目共同代表了矩阵计算软件的最新技术。MATLAB 经过多年的发展,得到了许多用户的投入。在大学环境中,它是数学、工程和科学入门和高级课程的标准教学工具。在工业领域,MATLAB 是高效研究、开发和分析的首选工具。MATLAB 具有一系列称为工具箱的特定于应用程序的解决方案。对于大多数 MATLAB 用户来说非常重要,工具箱允许您学习和应用专业技术。工具箱是 MATLAB 函数(M 文件)的综合集合,可扩展 MATLAB 环境以解决特定类别的问题。可用工具箱的领域包括信号处理、控制系统、神经网络、模糊逻辑、小波、仿真等。